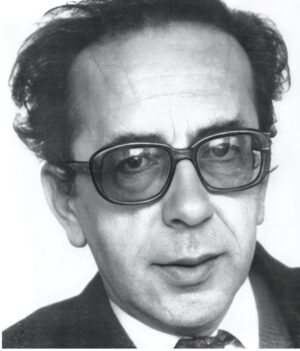

Ismail Kadare

Ismail Kadare is the most famous living Albanian writer. This is my translation of one of his best novellas, Kalorësi me skifter. Hope you enjoy it.

The Knight with the Hawk

By Ismail Kadare

Translated from Albanian

By Arian Koci

Translator’s note

I first read ‘The Knight with the Hawk” in 2002, on the London to Paris Eurostar train service on my way to interview Ismail Kadare for the BBC Albanian Service Radio. The novella had been published in Albanian a year earlier and, having bought a copy of the book in Tirana, I did not want to miss the chance of having it signed by Kadare, which he kindly did.

It was my first trip on the Eurostar and whilst making myself comfortable, I remember marvelling at the idea that soon the train would run under the English Channel and after twenty minutes of high-speed travel through the Eurotunnel, it would emerge in France. Half and hour later, I would be in Paris making my way towards the city centre and the flat of the greatest living Albanian author.

As if this was not exciting enough, I found myself gripped by the novella. It was set in Lezha, in northwest Albania, where I had grown up. I knew that its centrepiece, the hunting lodge, was still there, barely three kilometres south of the town. Memories of several school day trips on its grounds came flooding back and I could almost smell the sweet fragrance of the blossoming orange trees in its garden. The building itself was magnificent. Built of stone and wood it had a rustic charm that is accurately described in the story. At the end of its large yard there was a small bridge leading to the main dinning hall. My mother later told me that the lodge had been built by Benito Mussolini’s son-in law during the Second World War and, as an 11 year old, I remember being awe struck by the thought.

All these things were going through my mind as I was racing through the pages. Although I was treading on familiar ground, Kadare was opening a new door to my world and forcing me to look at it from a new perspective. My childhood image of the hunting lodge as an idyllic place with blossoming orange trees in the garden was slowing fading away and being replaced by a more sinister apparition. In Kadare’s story, the stone walls and the dark panelling wood of the building hid many secrets. The hunting lodge had been built not for relaxation but for intrigue. Situated at the edge of a marsh, away from civilization, it occupied a mystical place and seemed to be a time port through which the essence of crime would effortlessly travel from one world to another.

We learn in the story that the lodge was primarily built as a trap to assassinate the Italian Viceroy of Albania, Francesco Jacomoni, or maybe the Fascist Italian leader, Benito Mussolini himself. There are no clues to the plot, only a sign, the painting of a knight with a hunting hawk resting on his shoulder. The narrative of what happens to the painting and the lodge itself reflects the history of Albania throughout the second half of the twentieth century. We see it being occupied by the Italians, then the Germans. After the war and the communist take over, the hunting lodge becomes a secret negotiating venue between Albanian and Yugoslav representatives. The historical journey however, is only secondary to the story. It only serves as a backdrop and one gets the impression that the intrigue could have happened anywhere. And that is the genius of Kadare. His stories transcend time and cultures. He descends to the depths of human spirit, peeling away the layers that make us different and uncovering what we all have in common.

At first, after finishing the book, I did not think of translating it. I simply wanted to prolong the pleasure of a good read. Besides, I thought, how does one do justice to his work? Translation had been one of my subjects at the University of Tirana in Albania twenty years ago, and I had published many translated short stories in various journals. Kadare, however, was another matter. His writing is direct, intense and colourful. It has an internal rhythm and an economy of language that is almost poetic. Consider the following paragraph, where Kadare describes the impression that the newly built hunting lodge leaves on its owner, Count Ciano:

Mr Mohr, the architect, travelled twice to Albania, in spring and in summer to oversee the work. … He chose the stones himself, especially the ones to be used at the main entrance and the fireplace. They were old stones; their nakedness enhanced their grandeur and silence. They had an understated grandeur, as if from another world which always seemed aloof and mysterious. And the Count liked that. The wood panelling the walls and the ceilings were cut from local forests. It enhanced the subdued sombreness of the stones which was understandable. But the Count liked that too.

And, as in every translation, I worried over every word. The age-old dilemma would often raise its head. Do I carry out a direct and faithful translation of the work or allow myself the freedom of interpretation? I suppose, this, above all, captures the essence of the translator’s art. For instance, in the above paragraph I have translated the grandeur of the stones as being understated. Kadare uses the Albanian word te drojtur, which means timid — and as in English the word mostly refers to people rather than objects. But it seemed to me that Kadare’s choice of the word had more to do with a discreet display of grandeur than timidity and so I decided that understated was more appropriate. Many more words and phrases in the story have given me equal amounts of headache and joy and this is not the place to go through all of them. Suffice to say that the enjoyment of finding in translation the right meaning and the emotional nuance of the original sentence was thrilling enough to make the effort worthwhile. This is one of the few English translations of Kadare’s works from the Albanian, mostly have been carried out from the French. If I have managed to convey to you some of the pleasure I experienced when I first read this story in Albanian, I shall be a very happy man.

The Knight with the hawk

On April 7 1939, at six in the morning, the painting ‘The Knight with the Hawk’ stood hung at a museum in a Scandinavian country. Some two thousand kilometres away, in a town in central Italy, architect Ernesto Mohr was deep in sleep after a restless night caused by a painful spleen. Somewhere in the east, on the other side of the Adriatic sea, a seventeen year old Albanian, Bardh Beltoja, a student at the local grammar school, was also asleep in his house at 27 Royal Street in the city of Durres.

A military plane flew along the Albanian coast somewhere between Durres and Shengjin. From inside the cockpit, Count Ciano, piloting the plane, observed the shoreline below covered in trees and marshes. A terrific place for a hunting lodge, he thought. It could have several rooms and would be perfect for torch-lit dinner parties with friends from afar.

He thought of the smooth right buttock of Baroness Scorza and the latest surprise on it, the small scorpion she had tattooed especially for him, and smiled. Then, he turned his plane to the right and looked down as if to make sure that the warships, which would soon reach Albania, were still approaching the coast below.

Like many beings and things in life which often come together only to fall apart again, the mediaeval painting at the Scandinavian museum, the architect with the spleen condition, Count Ciano and the Albanian youth, Bardh Beltoja, were suddenly, on April 7, 1939, bound together with an invisible thread that could have only been spun by death. The knot would only unwind seven years later.

2

The construction work for what later became known as ‘Lezha Hunting Lodge’ began in October of the same year. In early 1940 the foundations had been laid. The building looked bleak, half a monastery and half an Albanian highlander’s kulla, a hybrid that many thought impossible.

Mr Mohr, the architect, travelled twice to Albania, in spring and in summer to oversee the work. To his surprise, the flights eased the spleen pains. He chose the stones himself, especially the ones for the main entrance and the fireplace. They were old stones; with a nakedness that enhanced their grandeur and silence. They had an understated grandeur, as if imported from another world which always seemed aloof and mysterious. And the Count liked that. The wood panelling the walls and the ceilings were cut from local forests. It enhanced the subdued somberness of the stones which in itself was understandable. But the Count liked that too.

3

The architect made his third and last journey in autumn. The Count was in a hurry. After a quick inspection of the interior, he ordered the last changes. From the different chair samples on offer, he chose the simplest ones which were like stools with back support, similar to those that the Albanian highlanders called shkamb. They looked more like flat stones where travelers would sit upon on road sides. He ordered all marble cladding of the fireplaces to be taken away, including the main one in the hall, in order to maintain the ‘tragic character’ of the Balkan fireplaces. For bed covers he chose the blankets made of sheep wool which he thought were a remnant of Homeric times. He took down all the mirrors, except for the bathroom ones. It’s not a good idea to have mirrors near marshes, he said without looking at anyone. The Count’s entourage waited for him to explain the enigmatic phrase, but he didn’t oblige. Instead, the faint smile on the Count’s face appeared to suggest that the architect had, once again, expressed a common understanding with him for which the Count was quietly proud.

Nevertheless, while walking across the inner yard, Ciano’s assistant, seeing that the architect was a distance away, whispered to the Count that he valued the architect’s opinion when he said that the ‘dramatic character’ of the Balkan fireplace was closely linked to the conversations taking place around it, such as discussions about funerals. However, he wanted to remind his lordship that the fireplace was not going to be part of an Albanian highlander’s room, but a sejour bringing together the Count’s guests, which needless to say, included the crème of the aristocracy from across the sea.

Whilst the assistant was talking, a thought flashed in Ciano’s mind. There was nothing more exciting than the contrast between the cold somberness of the stones of a room and the warm silk of the lingerie of women who would travel from afar to make love. Now he liked to think that the architect had understood his secret desire. Whilst pretending to tone down the ambiance of the rooms in order to give the impression that anything but love could take place there, in fact he was suggesting the opposite.

Ciano did not reply to the assistant. By now they had reached the main hall, the banqueting hall. The architect looked at the torches that were going to be put up on the walls. They were made from beaten copper and iron and were similar to the ones at the main entrance which looked like torches often found outside inns (mediaeval inns on dangerous roads, as the architect had described them.) The architect was less critical than expected about the torches, probably because his mind was on something else.

There should be a painting here, he said, standing with his arms crossed and looking at the wall above the fireplace. It should be the only painting in this hall, he added. Everyone looked at him wondering what marvel or mischief he was going to come up with this time.

While waiting for the architect to come up with the name of the painting or the artist, to everone’s surprise, he seemed to have lost his self confidence. They soon understood the reason. He could not remember the name of the artist or the painting that he wanted on the wall. Was it possibly by Rembrandt or Roubens, or another of their contemporaries? He thought the painting’s title was ‘The Knight with the Hawk’, but he was not sure of this either. He had seen it many years ago, in his youth, at the museum of a Scandinavian city, the name of which he also could not recall either. The only thing he was sure about was that it had been a city and not the capital.

“The painting depicted a knight holding a hunting hawk… The knight had been invited to take part in a hunt … he had a mysterious look that was open to many interpretations… So, as I recall, he was going on a hunt … nevertheless his face was very enigmatic”.

“I can’t imagine another painting on this wall”, added the architect. “It’s the painting of someone invited to join a hunt, do you understand, my lord? This is the essence of everything. The suspicion and the mystery on his face is the mystery of every distant traveller, of a guest, be it human or a ghost… After all, one never knows what the guest is thinking about.”

How wonderful, thought the Count.

The architect took a deep breath before finishing his thought. “His Lordship had all the means of finding that painting. He had Embassies, informers in those countries. If he could not buy the painting, he could order a reproduction instead. This was his wish. And now, with his Lordship’s permission, he would like to rest. His spleen was more painful than ever”.

“Have a rest, my dear”, said Ciano, resting his arm on the architect’s shoulder. “Your wish will come true. I promise”.

The architect nodded in appreciation. He looked very pale.

4

The bedrooms and the rest of the lodge were furnished in three weeks. The chimneys were tested soon afterwards. By early December everything was ready. Unexpected state engagements had prevented Ciano from inspecting the lodge one final time, which in the fashionable circles had begun to be called the Count’s ‘Albanian whim’, or ‘the Albanian folly’.

His envoy inspected everything diligently, from the woollen bed covers of the Count’s suite, to the little torches on the sides of the small wooden pier built to moor the boats.

The invitations for the first hunt had been sent out for some time throughout Rome, which in the last two years had become known as the capital of the United Kingdom of Italy, Ethiopia and Albania. The first inevitable resentments of those left out had already started too.

Contrary to initial plans, the Count arrived at the hunting lodge only a few hours before the guests. Instead of having a look around as expected, he said he needed a rest. He said he only wanted to look at the painting that had arrived two days ago from Scandinavia. He stood motionless in front of it for a while. The flickering flames from the large fireplace opposite seemed at times to reach towards it. Was the illumination of the flames on the painting an accident, or was it all part of a genius design? The Count could not fathom the expression of the man invited to the hunt. The flicker of the flames seemed to turn its mystery on and off.

Pity the architect could not come. He had been bedridden for three weeks and was unlikely to recover. The architect’s illness and his lack of explanation of the meaning of the painting became topics of conversation and were often mixed with other stories about its reproduction. The knight of the painting had, it seemed, been invited to the hunt one last time. His eyes almost seemed to reflect this suspicion.

The Count felt he was approaching one of those rare moments when he could understand the hidden meaning of art. There was a real uncertainty in the knight’s eyes; a frozen uncertainty which was ennobled by sadness and fatality. He had just received an invitation to the hunt and although he suspected something might happen, he would still go … towards his fate.

No, thought the Count, just as he did when he first read that explanation. These mediaeval tales do not happen any more. He was clear before God, he had never intended to invite anyone to a trap.

No, he thought again, and immediately felt sorry that the architect was not coming. Only he could set him free from these maddening suspicious thoughts. He could explain, for instance, the sadness in the knight’s eyes and what had been so madly disappointing about that invitation, (perhaps a woman, the host’s wife, who having promised eternal love, now wanted to dispense with him.) Such disappointment forces one to think that dying might not be a great loss after all.

No, said the Count for the third time. The poised sting of the scorpion tattooed on Baroness Scorza’s right buttock offered no useful explanation either. Perhaps the architect’s disabling illness was the key to everything. Better than his presence, it was his absence that explained everything. He has sent the anguish of his death through this painting. He has done it modestly and naturally; like a man who turns down his invitation with a note on the back saying, ‘You are gathering but I am not going to be there. Enjoy the party’.

That was all. As he was taking his eyes off the painting, the Count felt he detected one last thought coming through the knights eyes: would anyone regret his death, or was it going to be ‘lost’ as Albanian highlanders would say. Suddenly he felt tired, and as if by command, he turned away from the painting and went to lie down.

5

The first guests arrived late in the afternoon, before dusk. Sitting up in bed he could follow the irregular noise of their footsteps on the cobbled yard. They were talking to each other, surprised of course by the journey by boat from the small harbour at Shengjin. The count looked at the time. The torches should have been lit by now, although there was still daylight. They were tied to posts in the water as markers for the boats. By nightfall the light of the torches would be twice or three times as impressive. The glass of both doors leading to the small yard in front of his suite was misty so he could not make out the faces of the guests.

The noise of a car either announced the arrival of yet more guests who could not endure the boat journey, or of Albanian guests arriving by road from Tirana. The first group was probably saying to the second one: you did not come by sea? So you missed the torches on the lagoon? What a pitty! It was such a view, so…how can I explain it …

He could hear the faint muffled noise of closing doors. It was the couples finding their rooms, or guests who had come alone or those who would announce that their wife or husband was coming the following day knowing full well that this was not the case. He also knew that questions about his wife would be whispered in the dimly lit dinning hall; do you know if Edda is coming? I don’t think so, she never liked hunting. Besides, they say she’s cross that the hunting lodge was not built in the south of Albania, near the port named after her, Port Edda, Saranda. You must have heard about it! Don’t you think this room is rather gloomy?

At first the rooms would look gloomy, the architect had said. That’s because, fickle as they are, people would need time to recall that they had not come for a ball but for hunting. The horizontal planks of dark wood panelled the walls in a tiresome monotony and were there to remind the guests that they were there to hunt, that is so say, to kill. There is no good pretending otherwise. They would only recover from this anguish after meeting up with other guests at the dinning hall for supper. Then everything would look warm and cosy; the lit torches on the walls, the burning fireplace and the hum of conversation, the architect had explained.

He’s a magician, thought the Count. He was sure that he had finally fallen prey to the architect’s genius. He did not even try to hide to himself the relief he felt at the thought that the architect was not going to be long in this world. Death would finally set him free from an ever growing enslavement which he had no idea where it could lead to.

Don’t pretend you are not aware of this, he said to himself as he stood up. It was time to go to the reception hall to see who had arrived and who was running late. There were many guests in the hall. Some were sitting near the benches covered in woollen rugs by the fireplace; others were sitting in the corners and the rest were wondering inquisitively around the room. Their anguish, caused by the bleak monastery-like rooms was slowly subsiding.

Ciano greeted them one by one, welcoming them and asking how they were settling in and whether they found the rooms gloomy. The last question, though uncomfortable at first for the guests, was the one that put them at ease.

He reminded them that they could have supper whenever and wherever they wanted to that evening, in the dining hall or in their rooms. The welcoming dinner would be the next day, after the first day of the hunt. He returned to his suite. Surprisingly, he felt tired and desolate. He sat in front of the fire. Outside, in the small yard he could see the silhouette of the sentry and further beyond the torches were flickering in the sea breeze. The last guests were arriving from Shengjin. Baroness Scroza could be among them.

At nine he got up for supper. Both main halls were full of guests. Some, as before, were sitting by the fireplace, others were mingling with wine glasses in their hands and the rest were already sitting at the table ready to order their supper. Ciano greeted the late guests; listened with faint attention to apologies about two missing guests, apologies which were whispered to him to make them seem important and he said he was sorry to hear the news. In truth he only felt sorry that someone else could not come, Curzo Malaparte. Despite his efforts, Malaparte had not managed to cross all of Europe in time for that evening.

The Count sat at one of the tables and, like the fisherman who catches other sea creatures together with the fish, he beckoned other guests standing near Baroness Scorza to join him. The words ‘informal dinner’ were often mentioned that evening and he lead by example. Occasionally he would wave at a late guest, women with freshly brushed hair would come and hug him. Old Marchioness Beetz, unabashed as ever, sat herself at the table uninvited.

“Would the Viceroy really have come had it not been for last minute engagements, or was it just a rumour”, asked Baroness Scroza taking advantage of the small confusion caused by the old woman. The count looked at the painting involuntarily. He quickly looked away and shrugged his shoulders.

“Jacomoni? I can’t say. Nevertheless, I would have invited him. He is the Viceroy of Albania and it would have been only natural for him to come, just as it was natural for him not to do so”, the Count replied. He was certain the same thing was being whispered about his father-in-law, the Duce.

There were always many people looking at the painting; it was the only one in the room so it naturally attracted attention.

“Did you see the painting”?, he asked the Baroness.

“Of course”, she replied smiling.

“Why do you smile”?

“People are talking about it, as well”.

“What are they saying”?

“Oh, gibberish, as usual”.

“Tell me, anyway”.

The deep voice of the old Marchioness, and especially her coughing, were the best cover to discuss these topics away from prying ears. She said the rumour was that Sweden or Iceland or whichever country had the painting, had asked a high price for it for political reasons and, in the end, it was decided to abandon trying to purchase the painting and a reproduction was ordered instead.

“Oh, really”? he said, chuckling in relief.

“How’s the tattoo getting on”? he asked quietly.

Her eyebrows arched upwards as if frightened by the extra brightness in her eyes.

“Very well”, she said. “Do you want to see it”?

“Of course, this very night”.

By now, not only the Count, but also she was looking in relief at the old Marchioness who was coughing her lungs out.

While listening to the woman, his gaze would occasionally glide towards the wall where the painting was. There were always people looking at it. This was understandable as it was the only canvas on the hall. Besides, everyone sought to find something about themselves in the knight. He had been invited to a hunt, which was what they all had in common. They would walk gently in front of the painting marvelling at the colours, or at least pretending to do so, and at the knight’s facial expression, but would not understand anything about its nostalgic suspicion born out of the fatality of his predicament.

The Count imagined some of them standing in front of the mirror getting ready for the journey and was sure that noone anticipated anything bad to happen. They could not be suspicious of all the palaces they visited and the dinners they attended.

“Galeazzo, what’s the matter”?, asked the Baroness softly.

He nodded as if to say ‘nothing’. Then he said he would wait for her at midnight when everything had calmed down. The guard in front of his suite would be been given advance notice.

She blinked slowly in agreement. He looked at her closely for a moment and was almost surprised to notice on her face something resembling female tenderness towards him. Instead of enjoyment, he was frightened by the thought.

6

The Count was aware that it was hard to sleep near marshes, just as he was aware that people always liked to find some unreasonable explanation for his insomnia. He poured the sleeping powder in a glass of water, drank it slowly and lifted the blanket that was half covering the Baroness. She was sound asleep. Perhaps only men had trouble sleeping near marshes.

Because she had put on weight, the tattoo on her buttock was slightly distorted, it looked bigger and lighter and not as dangerous as six months ago when they made love the last time. He recalled the tender look he had noticed in her eyes and for a moment it occurred to him that, for no reason at all, this was the way that venom levels increased and ebbed away in people.

They blamed the marshes for disturbing their sleep, but if the marshes could talk they would murmur the opposite; it was the people who, whenever they stayed near them, brought out their angst and horror on themselves. He imagined the sleepy surface of the water rippling in advance in pain for the pheasants that would splash down and die after being shot at dawn.

Despite the large number of guests, he had also brought with him that mysterious painting which now stood alone in the cold empty hall. He was almost certain that now with no people around it, the face of the knight on the painting would drop its mask and reveal its true feelings.

He wanted to get up and slowly approach the door to eavesdrop and unravel the enigma. If he suspected a trap, why had he decided to go on the hunt? What last hope was he hanging on to? Perhaps he had made up his mind and had reached a stage unknown to most people, the freedom of a helpless man.

Jacomoni had not come. Had he suspected something? Oh no, he sighed. No, no. No suspicion could reach a victim’s head if it had not been implanted there by the brain of the killer. And God was his witness that he had never harboured such dark thoughts.

He did not hide his malice towards Jacomoni and he envied his position as Viceroy. He even hoped to replace him one day. But never in that way. Galeazzo Ciano, Count of Cortelazzo, Viceroy of Albania. It has a nice ring and an internal harmony to it. He had mentioned this several times to Edda, which was the same as saying it to Mussolini. Ciano had expected him and no one else to shoot him in the back while hunting with dogs…

Perhaps this happened in that part of the brain they call the sub-conscience where other laws were at work. It was well known that in those areas, from childhood, almost everyone was a killer. Ciano had dreamed of the title of Viceroy since that April morning when flying his plane along the Albanian coast an hour before the invasion. Jacomoni had not been appointed by then and Ciano had seen Mussolini’s permission to carry out that symbolic flight as a promise.

That April morning, his aspiration to become a Viceroy had been entwined with the sorrow of the Albanian queen who, according to his spies, was at that very time leaving the country together with the king. On that intoxicating blue morning, when everything, including sorrow, looked beautiful and supreme, he was ready to believe that the loss of a queen was a necessary condition for providence to reward him the title.

His lust for her had been inevitable from the moment they had met. Everything around had been bright, luxurious, fragile and ambiguous. The marriage contract between the harshest king of Europe, the Albanian King Zog and the continent’s most beautiful queen, the Hungarian countess Geraldine. He, the foreign minister of Italy, as main witness. The rings twinkling full of mystery on their velvet cushions. The swan-like neck of the twenty-two year old countess. The short fair moustache of the king and the cold distant look of his eyes, looked like ice from another season. Almost like sick ice he had later thought.

He thought it was natural for him and the queen to feel attracted to each other in a ready erotic urge. He was the Duce’s son-in-law, she was a countess and standing between them was an ambiguous Balkan king. His eyes would occasionally come to life, as if to show that this highlander monarch who had been shot at and wounded twice, once in parliament and the second time in front of the Opera House in Vienna, was a descendent of a race that would kill you for trying to seduce his wife; and this made the affair even more thrilling.

And so, he felt it was not only natural but also inevitable that he, as the Duce’s son-in-law and foreign minister of Italy, should try and seduce the future queen of the small country that, with every passing day, was falling in Italy’s grip. It was almost part of his duties, something for which he could have faced criticism had he neglected it. You were untiring in your willingness to chase after any lady’s skirt and now cannot bring yourself to put in some effort for a queen? Yet, in spite of his resolve, he had not managed to evade criticism.

Two years later, Mussolini would look at him disdainfully in his large office while pointing at the copy of an interview that the Queen of Albanians had given to an English newspaper in which she mentioned something about the ‘exceedingly vulgar approaches from the foreign minister of a seemingly friendly country’. Ciano had turned red to the roots of his hair. ‘You creep’, had shouted his father-in-law. Ciano never understood whether Duce’s anger had been brought about by the temerity of his son-in-law to go after another woman, or his lack of discretion. And that had probably killed his dream of ever becoming a Viceroy.

But on that April morning, while flying his plane above Albania, Ciano had not been aware of the twenty-two year old Queen’s contempt for him. He was convinced that while fleeing the country, among other things she missed most, would have been the possibility of flirting with him.

The wild duck was getting away from the hunter’s gun sight … behind her remained the kingdom and the title of Viceroy. He again consoled himself that he could not have had both. And perhaps the idea of building a hunting lodge had come to him during a thought process in which the bird related name of King Zog, the swan-like neck of the queen and the cracking noise of a firing gun missing its target, were brought together in an impossible connection.

He turned in bed. In a mad rush, images were fast spinning in his head, the speed of which he could not control – the painting from the north, the face of the Viceroy and the woman’s tattoo together with her husband talking dirty while making love to her from behind, saying ‘whom did you have the scorpion done for, you slut, who’ …

Ciano thought that everything could be endured in this world, but not Jacomoni’s face. He despised his laugh, his short hair cut, the way his neck made him look so idiotic and how this accentuated by his shinning boots. However, he had never thought of going that far … to shoot him in the back. This painting, exactly this painting was the best proof of his innocence (now he was going through his answers in an imaginary interrogation.) Anyone intending to do such a thing would not have had this painting put in this hunting lodge.

“Bastard”.

The temptation to shout was so strong at he buried his face in the pillow. “You bastard” he shouted at the architect. “What devil possessed you to do this to me? Where did you find the courage”?

The answers were hazy. He didn’t remember the name of the painter, or the museum, or the country where he first saw the painting. Where had the architect found the courage to deceive him? Especially the other kind of courage, the big one, the courage to give him bad tidings, the announcement of a crime. No doubt, that courage came from the sick spleen. One only got such courage when approaching death. Also, the images of the whole of kingdom filled with suspicious invitations coming from all directions, could only come from the same source. Hurry, be the first to send out the invitation before the others do. Everything depended on who would be the first to kill the other, the guest of the host.

“Oh, you bastard”, the Count sighed. He had wanted to get out of bed for some time, to pull that painting off the wall and throw it in the bog. But his limbs disobeyed him. They had, by now, abandoned him and turned to sleep. In that depressing void there was only troubled waters and the sick spleen of the architect floating on them.

7

Two hunts, one for pheasants in the middle of February and the other for wild ducks at the end of March, revived the lonely hunting lodge by the marshes. The third hunt, announced for April, was postponed for no known reason. It was whispered that a meeting with Ribbentrop might have been the reason for the postponement. After that, it was said that the Duce had been for a visit after a difficult journey along the Albanian-Greek border. But none of these visits took place.

During summer, its roof was camouflaged with branches and leaves. There were suspicions that the English knew about the lodge and their air force was looking for it. At the end of spring the architect died and a year later Galeazzo Ciano was shot dead on orders of his father-in-law. He was taken to an isolated meadow and tied to one of the high stools. When the first three bullets hit him, his body almost did not move. His head fell forward slightly to the right as if he was looking for something underneath his feet, an insect or a lost hair clip. The fourth bullet covered his neck in blood like a red thick scarf, his head fell further and did not move again.

8

The investigators wandered for three weeks around the now abandoned bleak lodge that looked twice as gloomy. They investigated, photographed everything; the hunting rifles, the bullets, the small vanity mirrors left behind by women in the rooms, notes on diary pages, magnifying glasses, medicinal pills or powder, syringes, condoms, invitation cards.

They were under strict orders; not to overlook anything; the investigation had to be thorough, nothing should be neglected. Behind any trivial item or moment, no matter how seemingly insignificant, could hide the shadow of the plot against the Duce.

This directive increased the height of suspicion to previously unseen levels. It was accompanied by criticism for the lack of zeal that was similar to that meted out to children for mistakes they had not made but were thought of being capable of. One of the investigators, following a lead from a short note in the Count’s diary saying ‘tonight the scorpion comes’, had discovered that the ‘scorpion’ referred to Baroness Scorza due to the scorpion tattoo on her right buttock. Even then he had not been satisfied with the explanation. He was convinced that the tattoo could have been a secret symbol of the conspirators and after several trips to Rome had been able to find the tattoo artist. Frightened by the sudden arrest, during the first night of torture, the tattoo artist came up with the full list of people he had tattooed. He had also given unimaginable details that were not necessary for the investigation, such as how he had convinced the Baroness to sleep with him so that he could better design the tattoo and make love to her from behind so that he could pinpoint the correct place for her scorpion which after all, was meant to enhance the sexual pleasure of her partners.

After this important revelation, the investigator had hurried back to the Baroness, this time showing a lot less deference towards her. This had finally broken her down and she tearfully began telling him other intimate details not only of her own body and that of the Count’s, but also of his wife, the Duce’s daughter. This last information ended the investigator’s career and had him sent to prison from which he never came out.

What followed had been expected; the investigators were reprimanded for being overzealous and unfocused. The first investigation file to be thrown out was that of ‘the rapists of the wounded wild ducks’. In fact there had been two such rapists and the investigator was ordered to stop the case that was described as a ‘rare pathological matter unrelated to the investigation’.

A new line of investigation, based on meticulous facts, would have finally taken centre stage, had one of the investigators, the youngest one, not accidentally made a shocking discovery. At least one man and three women had been registered under false names in the guests’ list (which had been compiled with a lot of effort). This had been enough to restart an unstoppable guesswork. The latest suspicion spread quicker than August fires. Perhaps, not just four, but possibly half of the guests in the list could have given false names. And perhaps not only the guests, but also the hunt itself could have been a cover for other nefarious activities. Perhaps it was a dangerous mystical sect with a quasi political-military agenda; a secret Committee for the creation of Greater Albania; an international oil company set up not to discover oil but to hide its existence instead, or a male prostitution ring etc.

All these lines of inquiry were being pursued simultaneously. No one thought whether they contradicted each-other, or that the solution of one would mean closure for another. Instead, they were convinced that all of them were part of a chain. The theories were irregularly interwoven with each other like the skins of an onion in order to stop any penetration towards the labyrinth in the centre; the plot to assassinate the Duce.

They were not easily mistaken. They would get to the truth even if the investigation took a thousand years.

Surprisingly, the headquarters seemed to have forgotten about the investigators – it was neither hurrying them along nor slowing them down. Their meetings were becoming increasingly animated. So were the scene reconstructions. No one was sorry when the tattoo on the right buttock of the investigator playing the role of Baroness Scorza became infected. The investigators playing the role of the rapists of the wounded ducks could not wait for their turn, after which they would stay up till midnight to wash away the blood.

One of the investigators had the idea of creating an imaginary clone of Count Ciano’s conscience. And so they introduced a second actor, oblivious to the fact that in doing so they were reinventing the theatre of antiquity.

By now it was September. All the radios were broadcasting the capitulation of Italy, but this did not give the investigators any cause for concern. Convinced, as they were, that everything was part of a mise en scene, i.e. a cover to conceal the essence of the thing, the investigators interpreted the capitulation announcements as a victory for Italy. They were drinking champagne in celebration when they heard the main door being kicked open. In the nearby rooms they could hear harsh voices in Albanian and the bleating of sheep. After a while, Albanian peasants reached the door of the dining room. For a moment, each side stared at each-other in silence, in surprise. The investigators, dressed in strange clothes like theatre actors, were holding glasses of champagne and looking inquisitively at the door. First, a male goat peered through inside the room. The peasants followed behind.

9

Two hours after the arrival of the German forces in Lezha, three motorbikes, one with a sidecar, were speeding down the narrow road towards the hunting lodge. In the sidecar, Lieutenant Werner Wilms, kept worriedly consulting the map he was holding. Melancholy laden bushes lined the sides of the road. Suddenly, they found themselves in front of a gate, which at first sight looked like the entrance to an abandoned farm. The Lieutenant consulted the map once again and ordered the soldier riding the motorbike to stop. He jumped off first, the others followed, revolvers at ready in their hands.

That evening, the Lieutenant sat down to write a report which, together with other documents, was sent to the headquarters in Tirana. It said:

“On the condition of the hunting lodge of Count Ciano at Lezha (Lissus).

The building, though looted by the locals, still stands. Two peasant brothers who complained that the building was put up on their land and they were paid only half the amount of compensation promised, now keep their livestock in the compound which is already damaged by the looters. A dozen Italians still remain, locked up in the western wing of the building. Except for the cook and two servants, all the rest claim to be investigators, but resemble a theatre group from a lunatic asylum. Most of the time, their conversation does not make sense and their reasoning is very vague.

The painting ‘The Knight with the Hawk’ which is said to have been a sign or a warning about the famous plot to assassinate Benito Mussolini, has disappeared. Everyone confirmed its existence, even the exact place where it once hung, which is not difficult to figure out due to the slight marking it has left on the wall. In all probability, the aforementioned painting, as well as the expensive silverware and Venetian china could be in the houses of the local looters and, most if not all, could be recovered after a quick search. “

The Lieutenant read the last lines of the report carefully, considering whether to move them further up the report. He had accidentally learned which office was interested in such matters at the headquarters, and apart from guilt, he also felt apprehensive and suspicious. If he drew more attention to them, he would risk causing irritation which undue curiosity provoked. If he neglected them, it would be dangerous.

In an attempt to divert himself from the dilemma, he thought about what he had seen that unforgettable afternoon; the faces of the deranged Italians, the goats looking in amazement at their horns in front of broken mirrors, two peasants masturbating in a corner while sniffing in turn at a pair of ladies silk underwear they had found. Not so long ago, among all this, would have been the mysterious painting which, it was rumoured, had locked inside it the secret of a murder … With his eyes half closed, the Lieutenant was surprised that he could still shudder at the thought even after two years of terrible war.

It was bad tidings making their way from Mediaeval times to foretell a murder still to come … Like a time bomb set many centuries ago … Absurd, he thought. All this madness was surely produced by unhinged minds, like those of the actor-investigators.

10

Two years later, in the middle of December, two off-road vehicles stopped at the main gate of the hunting lodge. First the local peasants and then the inhabitants of the small town of Lezha had realised that the new communist state was taking over the whole country. This was the only topic of conversation in the three coffee shops of the small town.

The new government had made its presence felt in two places: the first one could be seen at the entrance of the town where a white sign on a blackboard read ‘Office of Extraordinary Taxation’; the other was less tangible, it was at a desolate clearing in the outskirts of the town, where it was rumoured that the enemies of the state were being executed by a firing squad. The former rich, and especially those suspected of enriching themselves during the war, were called in first and asked to return the money. Decisions were made on the spot, usually between beatings and cries for clemency ‘please, have mercy on me; I have given you everything I have’, after which the man, despite the bruises, would either leave off a sigh of relief at being told to go free, or taken to the desolate clearing because of his perceived insincerity.

The third change had taken place on the national flag; a small yellow star had been added above the double-headed eagle, but this had not been noticed by many. People had been used to changes on the flag recently; something was being added or taken off all the time and at the same place – just above the two heads of the eagle. The Italians had added the Roman fasces lictoriae, whereas the Germans, as soon as they set foot in Albania, announced the seemingly good news that they were returning the original flag to the Albanians, the one with the crimson red background and the back eagle in the centre.

Every day, on hearing the chimes of the bells of the Franciscans order, people would cross themselves and bless their providence that the sky was the same as before and no noise other than the weather disturbed it.

Surprisingly, the state’s take over of the hunting lodge, shocked the people. At first, they did not understand the reason for this and even tried to spread the bad news with a false indifference: you know, it was only a small hunting lodge, half a betting shop and half a brothel, they would say. And they would recall all what was heard or seen there before. Nevertheless, as they watched the furniture being brought in from the capital to replace the chandeliers and other furnishings, their anxiety had increased instead of ebbing away. And, with each passing day, they were beginning to understand the reason why. By making preparations for dinners and receptions, the state was showing its strength. It had grabbed the gold and had killed people out of fear, but the dinners and the secret negotiations were something else, a sign of self belief.

The hunting lodge was declared part of the larger ‘Dajti’ hotel of Tirana. The first official dinners were held in April, soon after the restoration was complete. The guests, most of whom were Yugoslavs or Russians, would ask the same question during the guided tour of the compound: Is it true that Ribbentrop has been here? Also Goering? Ah, it was only his nephew. Did they hold secret talks, as well as go hunting?

They were mostly interested in the latter suggestion, as though to convince themselves that the talks they had come for were also secret.

There had been a Rembrandt hanging on this wall? I don’t believe it! May be it was a reproduction. ‘The Knight with the Hawk’, was its title. They say it was central to the unveiling of a plot.

Comrade Rankovic could come to the hunt. Perhaps even Comrade Tito. One can’t have a proper sleep here. These words, often whispered by the majority of the guests, were first uttered by Milovan Djilas.

The young Albanian, Bardh Beltoja, in particular did not sleep well. He had stayed at the lodge for three days as translator for a Yugoslav delegation. The talks with the Albanian side had been difficult and tense. Old secret agreements had been mentioned which had made him shiver. ‘We’ll go to Comrade Stalin, let him be the judge’. Each side would say. ‘Of course, let’s go. Right now’.

At the end of the talks, on his way to Tirana, Bardh Beltoja had said he would never set foot in the hunting lodge again. Throughout the journey he had looked lugubriously at the passing scenes and had tried to forget what he had heard at the talks.

11

Four months later, Bardh Beltoja returned to the hunting lodge in Lezha. This time he was not accompanying any delegation. He had just come to hunt together with two officers of the Ministry of Interior whom he had met by chance at the Hunting Club in the capital. They had said he could go with them to shoot wild ducks at a restricted place. When he was told where this was, Bardh had smiled and had said he had already been there. He did not explain why and the officers had not asked.

It was December and the sky was dull. The conversation in the car was spasmodic, with deep abyss-like gaps.

The hunting lodge was empty. The night seemed to have descended sooner than expected and the three guests did not find it hard to go early to bed as they had to get up at three in the morning for the hunt. They returned at dawn. Two of them were dragging behind the body of the third guest who was already dead. The manager of the hunting lodge was looking in disbelief at the muddied wounds where blood could be seen seeping through. They asked for a telephone and in broken words announced the accidental death of the man.

The investigators accompanied by a forensic pathologist and a photographer arrived from Tirana the same day. They questioned the two officers at length, then took them to the marshes to reconstruct the scene of the shooting. They all returned covered in mud, took some more photos and tried several time to speak on the phone to someone at the capital, but all the lines were busy. It was rumoured that there had been changes to Party political guidelines.

In the twilight, all left, taking the corpse with them. The manager of the lodge looked on impassively as they got into the cars. Then he went to his house next to the lodge. His wife was waiting for him, trembling with fear. Will there be any more investigations? Or perhaps a search … like the last time?

He stared at her for a while as if he had not understood what she had been saying. Oh, no, he replied softly. He knew she was always frightened every time they spoke about such matters. She was scared about a small vanity mirror they had taken three years ago when the lodge had been looted.

No, he whispered. I don’t think there will be another investigation … Even this one … was more like the last one … more like theatre.

12

Over half a century later, in December 1999, Bruno Mohr, who was an architect like his father, with a similar spleen condition, arrived at Tirana airport on an AlItalia flight. As soon as he checked in at the hotel, he asked for information how to travel to the hunting lodge at Lezha and how to book a room there. The weather was cold. If he wanted to go hunting he would find all the equipment at the lodge. He could pay in dollars or lek. For security reasons he was advised to travel by taxi.

He arrived the next day. After leaving his bag in the room, he went out to see the compound. The wooden walls soaked in the winter’s afternoon glare. He screwed up his eyes like someone who is trying to decipher a hidden picture in front of him.

I have designed many buildings, but this is the only one which I feel had something mysterious, his father had told him a few days before his death. This rarely happened to architects …

He had spoken to him at length about his wonderings while designing the project. In those tired moments, he heard voices whispering to him: what are you doing? Are you designing a hunting lodge or a trap?

Bruno Mehr walked slowly into the inner yard and through the stone arches leading to the main gate where the torches had not been lit yet. Was it possible for a building to reflect the anxiety of its architect, be it even vaguely as in a spiritualism séance? He felt he could detect something, only to lose it again like a retreating frothy wave.

He had postponed for many years this trip simply to avoid these dilemmas. His father had told him … Go to the hunting lodge of Lezha in Albania and see what has happened there … I put up the warning sign … I saved my soul.

When his father was in less pain, Bruno had asked him what warning sign had he put up and who was it for. The architect would waver and say he did not want to burden his son’s young mind with dark thoughts. Besides, it would put him in danger. Sometimes, he said, ignorance is the best defence.

Still, every time the topic came up, he would add something new. “They said that the ancient designers of Egyptian pyramids always left behind an omen buried in a secret chamber in the centre of the pyramid. No one to date has ever discovered any of these omens and no one knew what they looked like. From the beginning I was tempted to do the same at the hunting lodge in Lezha. My soul demanded this. It was a vague calling that remained so even now. Still, among that vagueness, I managed to get hold of something. And there, in a painting from the north … is my omen. A knight with a hawk perched on his shoulder … a knight who perhaps senses the treachery behind the invitation … and still goes towards his fate … and now, don’t ask me any more questions”.

After his father’s death, Bruno Mehr started to pay more attention to the news to find out what was happening at the hunting lodge in Lezha. Twice he had wanted to go there to fulfil his father’s wish, but was prevented from doing so by other engagements. Once he thought that the execution of the Count, the owner of the lodge, would resolve the mystery. However, he could not relax. There was something wrong in the way evil flowed in that place.

He seemed relieved after the establishment of communism in Albania. All ties with the past had been cut off and this stopped the flow of secret curses and premonitions and of the winds that set them on their way. Besides, even if he wanted to, it would have been impossible to travel to Albania.

His father had been dead for fifty years when the Albanian dictatorship collapsed. The road to Albania was now open and, more than ever, he began to feel the urge to go there. You still have not been to Lezha’s hunting lodge …

In the large dinning hall, Bruno Mehr stood in front of the wall where the much talked about painting would have hung. The hotel manager, who by now knew who he was, was looking at him nostalgically. He had pleaded with Bruno Mehr to write something in the customer comments golden book. He had also said it would have been an honour to help him with anything he wished. For instance, he could offer him to stay in the Count’s suite. All important guests always asked this. But he deserved it more than anyone else.

Bruno Mehr had thanked the manager for all the offers and then had asked for only one thing: could he tell him anything about the secrets of this lodge … of a painting for example, which it was said used to hang on that wall.

Ah, a painting, had replied the manager. He had heard something about it. But someone else, the old manager, would know more about it.

Bruno Mehr had looked at him anxiously. Knew more, but would he talk to him? Wasn’t it dangerous?

The manager had laughed. That used to happen during communism. No one said anything. But now it was the opposite. People talked, often about things they knew nothing about. This little Albanian seemed to be like a sponge, like a black hole. It was now spurting out all the dark things stored inside.

Bruno Mehr turned and looked at the two managers waiting for him. He walked slowly towards them and sat down. The old manager, dressed in a black suit and bow tie that he had probably used at receptions during his time, was sitting very dignified as if waiting for the start of a ceremony.

The conversation soon led to the main topic. Many people had looked for that canvas. First the Germans, then the communists. But the painting could not be found. It would have been taken to Rome during the big investigation and examined centimetre by centimetre. Even the other painting, the fake one, had disappeared.

The other painting? Why a fake one?

It was a copy done in a hurry from memory that was used in the investigation. Every time the investigators would reconstruct certain scenes they would put the painting up. That was the rumour. I haven’t seen either of them.

Why was there so much interest in that painting?

Ah, many people had asked this question. One of them, for example was my wife, may her soul rest in peace. Why the interest? Who knows? It was rumoured that it contained a sign. It was the key to an enigma. Perhaps all this was fantasy, but these were the rumours. The painting foretold a murder. It foretold something that was going to happen, which was written that would happen. It was the same thing, but instead of being ‘written’, it was ‘drawn’.

“And”? asked Bruno Mehr quietly. “Did it happen? Did the murder take place”?

The manager shrugged. He did not know. They lived near the lodge, but they did not know what took place there. They could see the lights of the festivities and sometimes the torches on the marsh, they could hear the music, but they could not fathom what was happening.

“What was happening?”, repeated Bruno Mehr quietly. Of course, many things would have happened, but there had been no murder. He wanted to add that he had looked into this very thoroughly. He had sifted through all the newspapers of the time; he had probed all the archives and had found no trace of any murder. Even the investigation that had lasted for so many years had been about something else.

The two Albanians were listening to him intently.

“This must be true”, said the old one. “It looks like this did not happen at that time, in your time, but later …”

Instead of interrupting him to say that the time which the old manager had called ‘your time’ had not been his time, Bruno Mehr held his hands gently.

“Later … You said … later, please continue … This is about my father’s last wish … It is about the peace of his soul”.

He knew he had not made much sense, but he could not find any other words and continued.

There had been a murder, the manager said in a low voice, but it happened later, in our time.

In a few short words, which felt shrivelled as if coming from a deep freeze, he spoke about that bleak December morning when the body of the murdered man had been brought from the bog. He was young and had served as a translator at some secret talks several months earlier. They had invited him supposedly to shoot wild ducks and then had cut him down in the middle of the marshes. As soon as he had seen the body dripping in water and mud he had realised that there had been no accident, but a murder. The investigators said otherwise. But the investigation had only been illusory. The same happened every time in this wetland. As soon as the investigators arrived they seemed to leave behind the real world and enter another one. Enter into a theatre play …

What theatre? Who was the audience? Why?

The old man shook his head then looked up. Who was the audience? Perhaps God, who saw everything and pretended not to.

13

Bruno Mehr finally realised that he would not be able to sleep. He got up, turned the bedside light on and looked at the clock. It was three in the morning, exactly the time when half a century ago three people from the capital had left towards the marshes.

His room looked on the marshes. He looked at the darkness outside for a while in vague hope and nostalgia, as if asking for help. He almost believed he was addressing the darkness: “you know my father better than I. You’ve communicated with each other when he was here”. He, his son, had been too young to understand what his father had told him about his agony. That darkness, older than the world itself, perhaps understood this better, that which no human mind could fathom.

There probably had been a moment when they had touched, a moment in time, when the sign had passed from one world to the other. And thus, the murder plan that has been fluttering in the wind from medieval times, had accidentally dropped through, like a migratory being, into the drawings and the design of his project.

There’s no point, he said to himself. No point carrying on with the questions: how had his father captured the sign and who was the warning for?

Don’t push it, he said to his brain. For beyond lay a horror that was best left unknown. There is a reason why the locals here describe the process of pulling oneself together as ‘to call on your mind’, or ‘collect your mind’, which reminds one of the act of tying up a beast.

He should take it easy. This was a crime producing time. And if the essence of crime, like an indestructible windswept creature, moved from one world to another with no regard for social order or nation, then it meant that times were similar to each other.

Murder had first fluttered round Mussolini, the father-in-law of the unfortunate Count, then around viceroy Jacomoni; it had swirled round the deposed King Zog of Albanians (the invitation for a secret meeting after his overthrow was still in the archives of the German Foreign Ministry), then to the Yugoslav communist dictator Tito and, finally to the Albanian dictator who had twice sent his double to the hunt because he was convinced he was going to be killed according to a plan he had devised himself.

All this, to Bruno Mehr’s, surprise, seemed easy and understandable. In the end, every invitation had always had a degree of death in it. Suddenly, he shivered at the sound of a rustling noise underneath the door. He got up in a haze from his late sleep, walked to the door and pushed down the handle. There was indeed a hunting invitation.

It was still half-dark and he could not read the words very well. It was a hunt arranged for an important occasion, perhaps for the Stability Pact in the Balkans or simply the end of the Kosovo war. The hunting clothes could be rented at the lodge. The gear as well. For a moment he thought he would only need a hunting hawk. Possibly the lodge could provide one.

When he awoke in the morning, he remembered the dream and looked at the bottom of the door where he thought the invitation had been pushed through. There was something there. He walked slowly towards it, picked up the white paper and read the message: ‘According to the registration book of the lodge, the man killed on 19 December 1947 was called Bardh Beltoja’.

Before leaving for Tirana, Bruno Mehr asked the taxi driver for the way to the nearest Franciscan church. There he lit two candles, one for his father and the other for the unknown dead man.

The end